| | | |

|

The Atomic Orbitals

Atom in a Box

Real-Time Visualization of the

Quantum-Mechanical Atomic Orbitals

|

|

|

What is Atom in a Box?

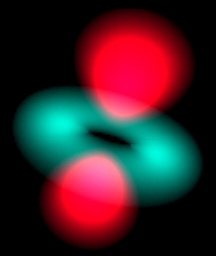

Atom in a Box is an application that aids in visualizing the Hydrogenic atomic orbitals, a prime and otherwise unwieldy example of quantum mechanics. Unlike other tools in this category, this program raytraces through a three-dimensional cloud density that represents the wavefunction's probability density and presents its results in real-time. The user interface is very interactive and provides a wide degree of flexibility.

The app can display a wavefunction as a picture of a cloud or use color as phase.

The version for iPhone and iPod Touch contains all 140 eigenstates up to the n=7 energy level,

while the iPad version can produce 2109 eigenstates up to the n=18 energy level.

How do I use Atom in a Box?

The bottom line is: PLAY WITH IT! Go ahead and try anything your heart desires.

This document is meant for those who want more details about the program but is not required reading.

|

|

|

What is Atom in a Box for?

Think of an interactive exhibit at a science museum. If it can evoke imagination or fascination or stir inspiration or simply teach, then it's doing its work, maybe entertaining along the way.

Atom in a Box is like that. It gives a visual answer to: "What is an atom?" You can think of the atom as the building block of chemistry and everything we can see and touch. It's an important scientific concept that people have struggled with since the ancient Greeks. Now, if you could hold an atom, like a toy in your hands, this App shows what it might "look" like. If Atom in a Box can inspire fascination with science, then it has done its job.

I think it looks cool too.

|

|

|

What is Quantum Mechanics?

One of the great advances in human knowledge of the

twentieth century is the birth of the theory of Quantum

mechanics. It has led to some of the most common technologies

used today, including the little transistors that make up the

computers you're using to read this. One of the mysteries it

revealed was the structure of the atom. Classical mechanics

could not properly explain the existence of the atom. Because

there was nothing to stop electrons from spiralling in to the

nucleus, it predicted that all atoms would immediately destroy

themselves in a spectacular high-energy blast of radiation.

Well, that obviously doesn't happen. Quantum mechanics

describes that the electron (and all of the universe for that

matter) exists in any of a multitude of states. The particular

physical situation determines what and how many states there

are. Borrowing from some of the techniques in mathematics,

physicists organize these states into a particular set of

mathematically convenient states called "eigenstates".

Eigenstates are good to use because what makes one eigenstate

different from another usually has a physical meaning. They

also can make an horribly difficult problem managable. These

and other phenomena in Quantum mechanics predict that

possiblities in physical phenomena have distinct separations

(e.g., "quantum leaps") and that energy transport exists as

indivisible packets, called "quanta". Hence the name: Quantum

Mechanics.

|

|

|

What are Orbitals?

By applying these techniques to the hydrogen atom,

physicists are able to precisely predict all of its

properties. The electron eigenstates around the nucleus are

called "orbitals", analogous to the orbit a planet occupies around a star.

We find that these states do not allow the

electron to crash into the nucleus, but instead find

themselves in any combination of these orbital eigenstates.

These orbitals' physical structure describe effects from how

atoms bond to form compounds, magnetism, the size of atoms,

the structure of crystals, to the structure of matter that we

see around us.

Visualizing these states has been a challenge because the

mathematics that describe the eigenfunctions are not simple

and the states are a three-dimensional structures. The

standard convention has the orbital eigenstates indexed by

three interrelated integer indicies, called n, l, and m. Their

range and interdependence comes out of the math in deriving

the eigenstates from Quantum mechanics and electromagnetism.

Special states, called eigenstates, have been found that, when properly summed together, can describe any allowed state of

the electron bound to the nucleus. By definition, they cannot be written in terms of one another (i.e., they are said to be "orthogonal").

These eigenstates have their own unique labels.

|

|

|

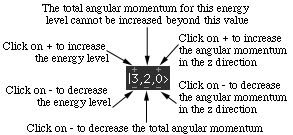

The first refers to the energy of the eigenstate, labeled by n.

n can be any integer starting at one, the lowest energy level, then two, three, and so on for higher energies.

Within an energy level, there are certain allowed distinct states of angular momentum which are identified by two integers, l and m.

l can range

from 0 to n-1 and identifies how much angular momentum the eigenstate has.

m can range from -l to +l, identifying how much of that angular momentum is in the +z-direction.

These three integers together uniquely identify every possible eigenstate, and are often written together in a Dirac ket: |n,l,m>.

(For full details, look in a Quantum textbook (a good one is A Modern

Approach to Quantum Mechanics by John S. Townsend), take a

course, or seek out a physics professor.)

The number of eigenstates for energy level is the square of that energy level's quantum number n.

So n=1 has one eigenstate, n=2 has four eigenstates, n=3 has nine, and so on.

For each eigenstate, Atom in a Box computes its wavefunction, a complex function of position. The magnitude squared of this function is plotted as brightness.

The app for iPhone and iPod Touch contains parameters for all the eigenstates up to n=7, which is the energy level for the highest energy electrons in the Uranium atom. That makes a total of 140 orthogonal eigenstates.

The iPad app generates, at run time, all the eigenstates up to n=18. So it can generate the complete description of up to 2109 eigenstates.

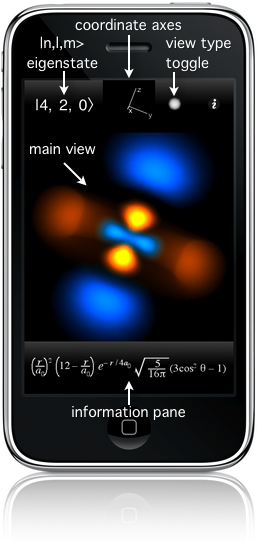

Changing the |n,l,m>'s

You can edit the |n,l,m> eigenstate by tapping it.

After it reappears at a larger size, overlapping the orbital,

you can step between these eigenstates by clicking on the + or - above and below the integers when available.

On the iPhone, tapping the upper left corner again returns the |n,l,m> to its home position.

On the iPad, tapping the orbital returns the |n,l,m> to its home position.

|

|

|

iPhone | iPad | Next Section

iPhone and iPod Touch user interface details

Main view

The primary display is the large square in the middle with the orbital in it. You can touch and drag your finger to rotate the orbital. Think as if you're poking your finger at it. If you're still moving it while you release, it will keep rotating. The small coordinate axes above the main display give a sense of reference to orient what you are seeing. Tapping once in the main display stops the motion.

To make it easier to connect the orbital with its coordinate system, double-tapping makes large coordinate axes, centered on the orbital, appear.

View type

The small circle just to the left of the  toggles the View type. The Grayscale display mode shows the three-dimensional probability cloud as a two-dimensional image, like photographing a cloud in the sky. toggles the View type. The Grayscale display mode shows the three-dimensional probability cloud as a two-dimensional image, like photographing a cloud in the sky.

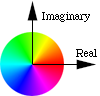

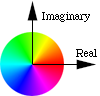

How color is mapped onto

the complex plane

Touching that circle toggles between Grayscale and Phase as Color. With Phase as Color, the phase of the wavefunction is translated into a hue of the cloud. The wavefunction is a complex valued function of position. Zero phase is translated into red, and increasing phase cycles through the color wheel, to yellow, to green, to cyan, to blue, to magenta, and back to red. Opposite phase corresponds to color complements, e.g., red and cyan represent opposite phases, yellow and blue are opposite, as are green and magenta.

Also with Phase as Color, you can see the time evolution of the wavefunction. Each eigenstate evolves in time at a rate related to its energy. For example, the states with m not equal to zero exhibit an electron flow around the z axis, like a small superconducting vortex.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Information pane

Below the orbital is a space displaying informative information relevant to the orbital. Tapping it advances it through four different display modes:

The mathematical form of the wavefunction being displayed as a function of spherical coordinates r for radius,

θ

for angle from the +z axis, and

φ

for angle in the x-y plane starting from the +x axis.

Probability distribution of the electron as a function of radius r, with tick marks for every Bohr radius, a0, a standard atomic length, and marked at the radius of maximum probability.

The energy of the electron in this wavefunction, along with that state's spectral label. Bound states have negative energy.

The three-dimensional time-independent Schrödinger equation, which is predicts all of these wavefunctions.

|

|

|

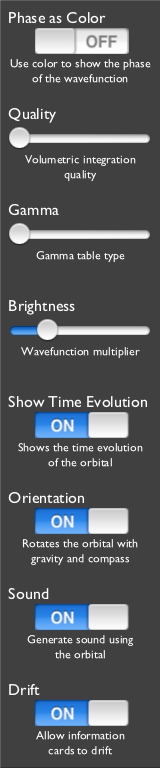

Settings Page

(via the  ) )

Quality

The code displays the wavefunctions by raytracing through the clouds and using a Simpson's rule integration technique to sum the contributions. As for all numerical integration, more samples usually mean higher accuracy (here a higher quality image), but more computation time spent, so the frame rate decreases (and the battery consumption increases).

The Quality setting allows you to adjust this tradeoff.

Gamma

The Gamma setting allows you to adjust the probability density to brightness function. This adjustment makes it easier to see the structure of some wavefunctions. The cutoff gammas cut off the brightness if the density is below a certain value but do no adjustment above that value, and the stepped gammas translate the linear range of density into a stair-stepped set of brightness outputs, giving a more isosurfacish look. (The name originates in the "gamma table" of computer video hardware; video hardware gamma tables are used translate the linear R, G, and B, outputs into a nonlinear voltage output to the monitor to compensate for the nonlinear response of screen phosphor.)

Brightness

After the wavefunction value is computed and before the Gamma table lookup, it is multipled by this Brightness factor. Raising this value will enhance low-probability details of the wavefunction, but often too much will obscure the brightest details. It is most useful with the various Gamma settings, above.

Fix a0

The Bohr radius, also know as a0, is a characteristic length scale of Hydrogen's ground state, sort of an atomic yardstick. This program automatically adjusts its size relative to the screen so that most of the orbital is always visible. Enabling this setting leaves that scaling size fixed so that the relative sizes of the orbitals could be seen.

Show Time Evolution

All wavefunctions naturally evolve in time. The time evolution of the eigenstate drives a flow of an electron around its nucleus, best seen in the Phase as Color mode. Mathematically a wavefuction in an eigenstate changes its overall phase as a function of time, but here you can see it visually.

Gravity

This program attempts maintain the orientation of the orbital relative to space using the device's accelerometer. It is easiest to understand by fixing the orbital rotation (tap once), then slowly rotating your iPhone or iPod Touch. The part of the orbital that was pointed up should stay up as you rotate the device around it. However, the hardware cannot detect if you face North after facing West, etc.

Sound

Interprets the wavefunction with sound.

Open Online FAQ

Opens a link to

this online resource with additional information about Atom in a Box.

Atom Wars

It is an homage to the classic arcade game Star Wars. You are in space,

firing your lasers on this atom of Hydrogen, which bumps its state up

according to the Wigner-Eckart theorem, which then fires back while

dropping down an energy state according to the Wigner-Eckart theorem.

When the atom drops to the ground state it can no longer fire at you.

You start with seven shields, and can exit anytime by tapping the score in the upper left.

Guide your ship around by tilting your iOS device left or right or forward or back.

Your score improves with fewer, more accurate shots.

Factory Settings

Sets all of the above settings to their defaults when you first open Atom in a Box.

|

|

|

iPhone | iPad | Next Section

iPad user interface details

Main view

The primary display is the large square in the middle with the orbital in it. You can touch and drag your finger to rotate the orbital. Think as if you're poking your finger at it.

If you're still moving it while you release, it will keep rotating.

To make it easier to connect the orbital with its coordinate system, double-tapping makes large coordinate axes, centered on the orbital, appear.

|

|

Settings Panel

Tapping the gear in the upper right  triggers the Settings panel

where you may shape vital aspects of the app's visualization and behavior. triggers the Settings panel

where you may shape vital aspects of the app's visualization and behavior.

- Phase as Color

With this setting off, the orbital is displayed in Grayscale.

This Grayscale mode shows the three-dimensional probability cloud as a two-dimensional image, like photographing a cloud in the sky.

The brighter parts of the orbital indicates where "more" of the electron, or at least its probability of being found, is.

How color is mapped onto

the complex plane

Touching this setting toggles between Grayscale and Phase as Color. With Phase as Color, the phase of the wavefunction is translated into a hue of the cloud. The wavefunction is a complex valued function of position. Zero phase is translated into red, and increasing phase cycles through the color wheel, to yellow, to green, to cyan, to blue, to magenta, and back to red. Opposite phase corresponds to color complements, e.g., red and cyan represent opposite phases, yellow and blue are opposite, as are green and magenta.

Also with Phase as Color, you can see the time evolution of the wavefunction. Each eigenstate evolves in time at a rate related to its energy. For example, the states with m not equal to zero exhibit an electron flow around the z axis, like a small superconducting vortex.

- Quality

The code displays the wavefunctions by raytracing through the clouds and using a Simpson's rule integration technique to sum the contributions. As for all numerical integration, more samples usually mean higher accuracy (here a higher quality image), but more computation time spent, so the frame rate decreases (and the battery consumption increases).

The Quality setting allows you to adjust this tradeoff with live feedback in the main orbital display.

- Gamma

The Gamma setting allows you to adjust the probability density to brightness function. This adjustment makes it easier to see the structure of some wavefunctions. The cutoff gammas cut off the brightness if the density is below a certain value but do no adjustment above that value, and the stepped gammas translate the linear range of density into a stair-stepped set of brightness outputs, giving a more isosurfacish look. (The name originates in the "gamma table" of computer video hardware; video hardware gamma tables are used translate the linear R, G, and B, outputs into a nonlinear voltage output to the monitor to compensate for the nonlinear response of screen phosphor.)

The display responds immediately to changes to this setting.

- Brightness

After the wavefunction value is computed and before the Gamma table lookup, it is multipled by this Brightness factor. Raising this value will enhance low-probability details of the wavefunction, but often too much will obscure the brightest details.

The main orbital display responds immediately to changes to this setting.

It is most useful in coordination with the various Gamma settings, above.

For example, it effectively will adjust and push the isosurfaces of the Stepped modes of the Gamma adjustment.

- Show Time Evolution

All wavefunctions naturally evolve in time. The time evolution of the eigenstate drives a flow of an electron around its nucleus, best seen in the Phase as Color mode. Mathematically a wavefuction in an eigenstate changes its overall phase as a function of time, but here you can see it visually.

- Orientation

This program attempts maintain the orientation of the orbital relative to space using the iPad's accelerometer and magnetometer.

It is easiest to understand by fixing the orbital rotation, then slowly rotating your iPad. The part of the orbital that was pointed up should stay up as you rotate the device around it.

The effect is as if the orbital was gyroscopically stabilized in space, and you are rotating the

iPad around that orbital.

The other user interface elements will also remain upright if you rotate the iPad from one landscape orientation to the other.

- Sound

Interprets the wavefunction with sound, but also toggles other sounds of the user interface.

- Drift

Directs the information cards to drift when they detect non-activity.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Information Cards

Tapping the info  icon, residing in the upper left corner,

activates all information cards not yet visible.

Each informative card displays information relevant to the orbital, each in its own way.

Once visible, tapping once has that card describe itself, but we give additional description here: icon, residing in the upper left corner,

activates all information cards not yet visible.

Each informative card displays information relevant to the orbital, each in its own way.

Once visible, tapping once has that card describe itself, but we give additional description here:

The three-dimensional time-independent (in Grayscale mode) or time-dependent (in Phase as Color mode) Schrödinger equation, which is predicts all of these wavefunctions.

The energy of the electron in this wavefunction, along with that state's spectral label. Bound states have negative energy.

Probability distribution of the electron as a function of radius r, with tick marks for every Bohr radius, a0,

a standard atomic length based on Hydrogen's |1,0,0> state, and marked at the radius of maximum probability.

The mathematical form of the wavefunction being displayed as a function of spherical coordinates r for radius,

θ

for angle from the +z axis, and

φ

for angle in the x-y plane starting from the +x axis.

The app calculates these equations on demand for both the

display in this card and to draw the orbital display.

A description of the application that is displaying the orbital, but two taps leads to

this online resource with additional information about Atom in a Box.

These information cards exist in the same three-dimensional space as the orbital itself.

Each card starts out on the front surface, but left to itself each will drift around the orbital and behind it.

Tap the card to bring it to the foreground.

|

|

Previous Section | iPhone | iPad

|

|

|

Behind the Scenes - How does this App do what it does?

The simplest brute force way of doing it, like how one might do it in Mathematica, would be to fill a large three-dimensional array of values using the mathematical solution of the wavefunction. Suppose you wanted a resolution of 256 x 256 x 256 in x, y, and z. Well, that's a little big, so you can probably interpolate from 128 x 128 x 128. That's about 2 million elements, each of which should require at least single-precision floating point numbers, which are 4 bytes big. Then that table would be 8 megabytes big. Of course, the wavefunction is complex, so that requires two floats per position, so that's 16 megabytes of data. And then you have to rotate your coordinates and raytrace through all of that. Even doing just an isosurface of that data can get slow without special hardware.

So, obviously, that's not it, because this entire application requires barely over a megabyte, much less than 16 megabytes. Another way might be to compute the wavefunction only when it is needed, so minimal data space is required. Well, you can have a look at the equations that the program displays. They have cosines, sines, and exponentials, all of which are nasty to numerically evaluate over and over again.

So what's the trick? In a programming tour de force for speed, this code utilizes lookup tables to an extreme. All operations more complicated than add and multiply are done using tables. That is, divides, square roots, exponentials, cosines, sines, arctangents, hue to RGB, etc. are all deep inside a combination of tables. And the tables are folded up in such a way so that all the tables used at any one time can fit inside the Level 1 cache onboard the processor.

So why did you do this?

The Mechanical Universe is a series of videotapes produced at Caltech that runs the gamut of first year undergraduate physics. It's an excellent source for visualizing and understanding basic concepts in physics. In one episode near the end, entitled "Atoms to Quarks", they show probability density clouds for the n=1 and 2 states, and stop at the |3,2,m> states. I loved it, but it all goes by very fast. The tapes date from the 80's, so I'm sure they slowly computed all the images on some computer and dumped them to videotape frame by frame. That's the only time I remember seeing the orbitals plotted as probability clouds. All the other portrayals of orbitals I've seen are scatter plots and single isosurfaces, which really hide a great deal of the structure of orbitals, or, even worse, just the Ylm spherical harmonic functions from Mathematica without the radial dependence.

So I decided that I wanted to generate volumetric (i.e., clouds) plotting of the orbitals in real-time on my computer. My earliest attempts were on my //ci (68030 at 25 MHz) back in 1994, but there I only got as fast as one frame per minute (!) with no tables. My first PowerPC attempt with tables was in 1995, but it failed miserably (I wasn't using the tables correctly). Then in 1997, I resurrected the code and was a lot more careful and got Standard 3D and Red/Cyan 3D working and working fast. In January 1998, while I was at the American Association of Physics Teachers conference, I figured out how to quickly translate the phase of the wavefunction into color using tables in 1998.

Why the funky grayscale look?

Well, it's grayscale for two reasons: 1. Anything other than grayscale around the orbital is very distracting and hurts some people's eyes after a while. 2. It makes the color in the Phase as Color mode stand out more. So the theme I thought of here was like a piece of stereo equipment.

And as for the funky part: From 1992 to 1994, I worked for a company, later known as MetaCreations, and was one of the two programmers who wrote Kai's Power Tools, a set of filters that plugged in to Adobe Photoshop for artists and advertisers. Besides doing neat things with images and being the first filter set with real-time previews, it had a very 3D-ish interactive user interface, coded by us two programmers (the other one still worked there until 2000) and designed by Kai Krause (he's done Yes album covers, among many things). Some users thought the UI was psychedelic (almost literally). So, I suppose my UI artistic style was influenced by my experience working with the people there, but perhaps I'm a little more reserved (and definitely more physics oriented).

Are there any easter eggs?

In the iPhone version, yes, the one easter egg is now a feature: it is Atom Wars.

Thanks goes to Robert M. Zirpoli III for critiquing the Mac version of this program. And thanks goes to John S. Kiralla for letting me use his iPod Touch for development.

|

|

|

Atom in a Box for iPhone, iPad, and iPod Touch

|

|

App Store release of Atom in a Box for the iPhone and iPod Touch.

|

|

App Store release of Atom in a Box for the iPad.

|

|

|

The orbital will reorient and interact using

the multitouch interface and accelerometer of the iPhone, iPad, or iPod Touch.

Quantum mechanical data is presented graphically and mathematically

via the iOS's intuitive user interface.

See the App Store for pricing and availability for your country.

|

|

|

Version History

|

iPhone and iPod Touch

|

iPad

|

|

|

|

v1.0.6: March 30, 2011

- Updated for compatibility with iOS 4.2

- Rotates the orbital with two-finger touches

- Optimized for recent iOS devices,

yielding up to 25% frame rate improvement

- Fixed minor bugs when reactivating sound

v1.0.5: July 1, 2010

- Updated for compatibility with iOS 4

- Sound for listening to the orbital

- "Atom Wars", formerly an easter egg, has been enhanced with sound

and accelerometer control and improved graphics so that it is now a feature

v1.0.2: June 17, 2009

- Recompiled with the SDK for iPhone OS 3.0 to verify compatibility, leading to:

- cosmetic edits in the Settings page

- frame rate improvements in Phase as Color mode

v1.0.1: August 19, 2008

- New online frequently asked questions web page via the new Open Online FAQ button.

- Regulated the atom's expansion on launch to occur when the UI is actually visible.

- Touching the x-y-z axes also rotates the orbital.

- Automatically detect if the accelerometer data triggers a collapse of the coordinate system, triggering coordinate system restoration.

- In case that detector fails, added restoration of the coordinate system to the Reset to Factory Settings function.

- Altered table element tracking to prevent cosmetic errors when activating Reset to Factory Settings.

- Because accelerometer data enters AiB at irregular times,

rotation due to the accelerometer is now relayed and smoothed through the

frame driver.

- Settings page buttons changed to be more like other Apps, rather than the SDK.

v1.0: July 11, 2008

Atom in a Box for the iPhone and iPod Touch debuts on the App Store!

It is among the first 500 apps available at the App Store's opening.

|

v1.0.2: April 21, 2011

- Compatibility with iOS multitasking

- enters inactive state by pausing frame driver thread and disabling event timers

- reenters active state by waking frame driver thread reestablishing event timers

- "Drift" switch in a larger sliding settings panel and implementation for cards

- Corner user-interface elements dim after 30 seconds of inactivity and restore when any are tapped

- Changes to the display of the wavefunction's terms

- uses scientific notation when needed

- prevents unnecessarily large terms

- reduces, where the numerics allows, to their smallest integer values

v1.0.1: April 5, 2011

- Support for two-finger rotate

- Blocked a signal from iOS 4.3 from incorrectly stopping orbital sound

- No drift of the last touched information card

- Transitions for the appearance and disappearance of the coordinate axes

- Structural changes to use UIViews and UIView-based animations for information cards and other elements, which facilitated:

- Touch tracking for switches in the settings panel

- Descriptions of information cards revealed via page curl

- Flip rotation of UI elements when the iPad is flipped

v1.0: March 30, 2011

Atom in a Box for the iPad debuts on the App Store!

The entire app is rewritten from the ground up for the iPad, including

the orbital rendering routines

(vital to support the higher resolution of the iPad display),

the equation generators,

the user interface elements,

the touch interpreters,

the mathematical expression rasterizers,

and every design element.

The result is an immersive visual environment

that lives

in the same space as the atomic orbital.

Certain features became possible only with iOS 4.2, including complex use of Core Animation and Core Audio.

|

|

|

|

|